Miriam Gultholz-Feldman

Miriam Gutholc/Gutholz Feldman daughter of Grojnim (Groinim) and Brandla/ (Rabinowitz). Her 3 sisters all survived the Holocaust.

- Rachel/Roza - marrried Shimon Kempinski [from Konin] and moved to NY, USA

- Chana/Chanka -(moved to Israel and d. in 2018 ) married Yehuda Wittenberg

- Basha/Batya - married a cousin Meir Gutholtz

Miriam was known for her courageous jump from the train to Treblinka and her miraculous survival. Below is one of her testimonies.

I "Was" in Treblinka

The following is a memoir written by Miriam Gutholc/Gutholz Feldman that appears in Yiddish in the Ostrowiec Yizkor Book, published in 1971

It was January 1943, the year of the death and the might of the final remnant of Polish Jewry.

All of Congress Poland, including my home town of Ostrowiec, had already experienced the mass deportations of October 10, 1942.

About 2,000 people remained in town, many of them illegal—meaning that they did not have jobs. Rumors were going about that the German beast was preparing a new “action.” They were planning to murder the last remaining, tormented Jews, those who had concealed themselves under the worst conditions in various hiding places at the time of the first evacuation.

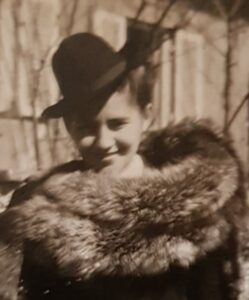

Miriam Gutholtz on right with her friend Ada/Etale Blajberg on wooden bridge in Ostrowiec before WWII

At first, people had believed they were being sent to work. The executioner himself thought up that lie. But they immediately realized the brutal truth: that those deported were cruel sacrifices to be gassed in the crematoria of Majdanek and Treblinka.

It was already after the mass deportations and slaughters of the larger Jewish communities in Poland, such as Lublin, Warsaw and many other towns. In the air one could feel that the great, cruel storm was hanging over our heads. The tragic day came. It was Sunday, January 10, 1943. On that terrible Sunday the remaining tormented Jews of the Kielce group were taken and murdered. During the deportation at that time, I went to Treblinka.

At five in the morning, the devil’s dance began. The ghetto was awoken by the SS, by Lithuanian and Polish police and other dark forces. To our great disgrace, the executioners did not even lack the help of the Jewish police.

Worn out and frightened, some dragged by force from various hiding places, everyone was taken to the transport, forced to the train station and the waiting freight wagons. It was very cold, the road was slippery, and those driving us forward did so without mercy. If someone fell, whether because he slipped or from exposure, he was immediately shot. The road was littered with the dead. Blood spotted the white snow, Jewish blood of the unfortunates who could not keep up with the driven crowds.

Along the entire way to our death train, the murderers rained down blows, which often knocked their victims unconscious. But the true orgy took place at the train station. As we entered the train, every smallest item of value, not to mention money and jewelry, was taken from us. We were ordered to remove our shoes and coats. And thus, half-dressed, we were pushed in, 120 people to a wagon. The dirty wagons had certainly only carried animals until now. We stood inside, pressed against each other, the small windows covered with barbed wire.

Outside, a blizzard raged and the frost stung. As soon as the wagon doors were locked from the outside, the train moved, and no one could determine in which direction we were being taken. A dead stillness reigned. The wagon was very stuffy, and everyone began to suffer from thirst. Some people fainted. People scratched the frost from the walls and with that rescued those who had fainted. All human needs were taken care of on the spot. We traveled that way for two and a half days in the crowded wagon, in the worst conditions.

On the third day, as the sealed wagon moved forward, the people, tormented to the point of death, noticed a sign, “Treblinka,” to which the train was coming ever closer. We knew very well what Treblinka meant for us. The train turned onto a side line, which was close to the death camp. There was nothing more to hope for. Death was all but certain. My only desire was to at least die an honorable death. Many people in the wagon still did not want to believe that our end was coming. The terror that the murderers had cast on their victims was so great that people trembled at the slightest thought of staging a resistance.

I told everyone that this was the time to jump from the wagon. Whoever can must jump, I told everyone. But my words fell on deaf ears. No one listened to me.

With difficulty, and thanks to the help of a family friend, R. Leibish Rosenberg, a Jew from Lodz who was no longer young, I succeeded in fighting my way to the little barred window. Before I jumped out, the martyr Rosenberg gave me courage with the words, “You are young. Jump and tell the world about our destruction.”

I jump from the train

His blessing was realized. The train was traveling quickly and I leapt as far from the tracks as I could. The guards accompanying the transport shot at me. I ran a considerable distance on the white, snowy field, and then I looked around to see where I was. I wasn’t wounded, but I was alone in the endless whiteness. It was a beautiful winter day, and on the horizon appeared a white, snowy forest. Everything shone, but I was in darkness. I felt like the last person on earth. I did not know what to do, and I regretted having leapt from the train. In such an oppressive mood, I was barely able with my last strength to drag myself to a peasant hut, where I asked to be allowed to warm myself a little. The peasants immediately saw that I was Jewish and they drove me from the house. As I ran away from them, I fell into a snow-filled hole and I was soaked through and through.

I had not eaten for three days, but I did not feel hunger. Darkness began to fall, and the night came quickly. Desperate and filled with fear, I barely managed to drag myself to the forest. I sat down to rest and fell asleep. When I woke up in the morning, I felt entirely frozen. I didn’t realize that my feet had been frost-bitten overnight in the forest. I left the forest and approached another peasant hut, which wasn’t far from the forest. I knocked, and a peasant woman opened the door for me. She let me warm myself, and she gave me hot coffee and bread. I warmed myself and began to feel a biting sensation in my feet. I took off my shoes, but I could not put them back on. My feet were swollen, and my toes were completely stiff.

The Christian woman gave me a large pair of shoes with wooden soles, and I gave her my own shoes. I bought from her an old coat with a peasant shawl, and since she had saved me, I went on the road to Kasav-Latzki, where there was still a Jewish ghetto and where I could hide, because it would have been very dangerous for her should I be found on her property. In such a case, the SS would burn down the entire place and kill the owner.

In the Kasav-Latzki Ghetto

It was about eight kilometers to Kasav-Latzki. This was the time of a Christian holiday, and from everywhere in the neighborhood, peasants were going into town. I blended among the Christians and in that way, I entered the town. It wasn’t hard to recognize the Jewish ghetto. I snuck in through an open slat in the fence, and in that way, I became a ghetto resident.

In the ghetto, sanitary conditions were very terrible. In addition, there was a typhus epidemic, and people were terrified of the SS men, who would come from neighboring Treblinka and kill Jews with axes in a bestial manner. I contracted typhus, and the only Jewish doctor there (a woman whose name I unfortunately don’t remember) saved me, even though no medicine was available. In the ghetto, I met a few other people from our transport who had jumped from the wagons as I had. I also met the Lublin rebbe’s son, Eiger, with a Jew from Lodz. They told me that they were preparing to return to Ostrowiec, where the rebbe’s entire family had been since the Germans had entered Lodz. The youth from Lodz had an Aryan appearance. But I was still sick, and I could not go on the road in such a state.

Back to Ostrowiec

The youth from Lodz with the Aryan appearance made his way to Ostrowiec, and told my parents about my condition. They immediately found a Christian, Marian Khamera, who came to Kasav-Latzki and looked for me in the ghetto. He brought me a train ticket. I disguised myself as a peasant woman, and, although I was suffering from fever and from extreme pain in my feet, I went on my way.

We didn’t travel together in the same wagon, so that if I were discovered to be a Jewish woman, no suspicion would fall on him. But he helped me a great deal and showed where I must change trains. To this day, I cannot understand how I succeeded in making my way without any documents and, in addition, so sick with fever, which could also have given me away. Moreover, at every station the SS checked people’s documents, and they arrested more than one person.

An interesting episode occurred at the Warsaw depot, where I was waiting for the next train. There was no place to hide. An old Polish woman came to me and after making an apology, she said, “You know, you look very Jewish.” “Yes,” I answered her, “a few people have told me that. It could be because in my village we all have dark skin.”

My heart was pounding, and I was all but certain that she was about to denounce me to an SS man or a Polish policeman, and that I would be taken away. The time until the train came appeared to be an eternity, but the train to Skarzshisk finally arrived. I pushed myself in together with everyone else, and that same evening I arrived in the Ostrowiece ghetto, where my family was waiting for me.

The state of my health was terrible. My feet had to be operated on as soon as possible. To my great good fortune, the well-known professor of Poyzner University, Professor Drevus, who was famous as a surgeon, was in the Ostrowiece ghetto, and he, together with Dr. Meir operated on me in his home. My return to health was greatly aided by the caring treatment of our informal doctor, Nachman Alman, who helped all of the sick people in the ghetto with great dedication. May his memory be blessed.

From the work camp to Auschwitz

At the end of March, 1943, the ghetto was liquidated, and the remaining tormented Jews were led to the kasharn [type of building] next to the factory. That was a camp guarded by Ukrainians, where we worked 16 hours a day in a state of hunger. At the same time, the overseers and Jewish police lived in conditions of the very greatest luxury. We remained in that work camp until the summer of 1944. When the front came closer, the Germans liquidated all of the camps in the area and sent everyone to Auschwitz. The number tattooed on my left arm is 16922-a.

From Auschwitz, we were sent in a transport to various camps in Germany and Sudetenland, until we were liberated on May 9, 1945.

I don’t have the strength to write about the humiliation, hunger, dirt and pain that we suffered in all of these camps. May our compatriots and readers forgive this gap in my writing.