Ralph/Rachmiel Waldman Hiding Testimony

I Survived the Nazi Hell in a Pit

Translation from Yiddish of his testimony written in the 1971 Yizkor book. Page 391-393

With a pen dipped into the blood of my heart, I want to sketch my horrific experiences as one of the “Romer commando,” who hid in an empty grave for a period of six months.

During the first evacuation of the Ostrowiec Jews in 1942, when they sent everyone to Treblinka, the Nazis selected 100 people and called them the “Romer commando,” to which I belonged. The mission of this commando was to clean out the empty Jewish houses, to bring all the possessions to a large camp, sort out all the objects, pack them up, and send them to Germany.

The “Romer commando” also had to bury the dead, particularly those which the Nazis, may their names be obliterated, murdered. Once, they killed 24 Jews, among them Yidel Aibeshitz’s daughter and her child. We brought all those who had been shot to the cemetery on Konow Street. Just as we were ready to put the bodies into the graves, two women (one, I remember, was Lola Erlich, she is in Israel) lifted herself from the bloody mass and we saw that she was still alive. It was late at night, and we helped the two women wash themselves off the blood, and sent them to the brick factory, where most of the workers were women. In the morning, they returned to the camp.

There were about 2,000 Ostrowiec Jews working in the camp, the majority of whom worked under the German commando, in the factory Zaklady Ostrowieckie, where they used to unload old steel. They put me to work in the construction area. Every day, when they took us to work, I noticed that there were fewer people among the workers, and I understood that the camp was slowly being liquidated. One early morning, when they were taking us to work, it was still dark outside, I went out of the marching lines and hid behind a wagon. When those marching were already at a distance, I ran into the field and hid among the tall corn stalks.

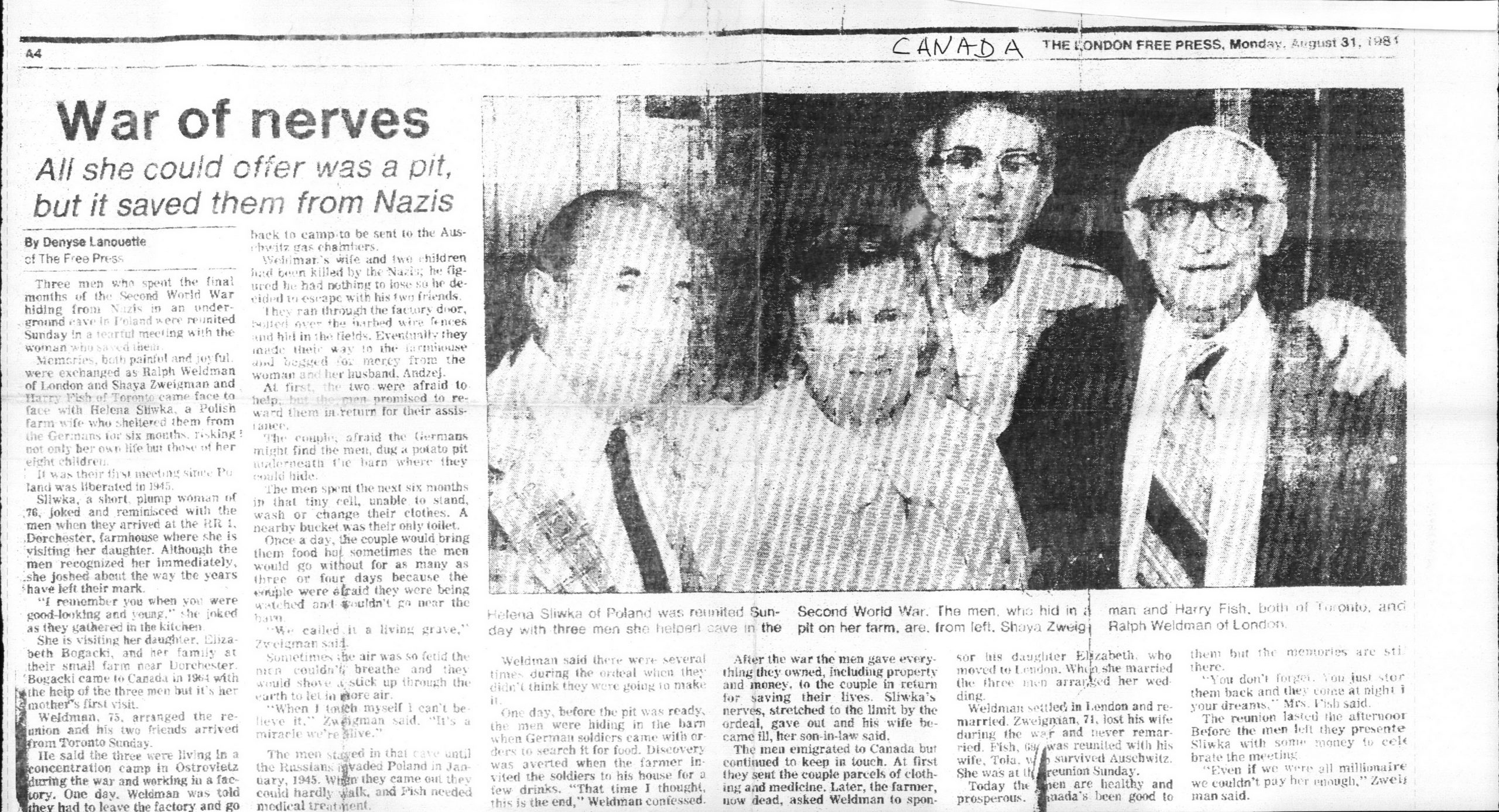

It was the end of summer, everything was budding and growing in the fields. I stayed like that for a few hours among the stalks, and later started to crawl on my knees so as not to be noticed by anyone. I thought of crawling to the closest village where I knew many of the peasants, and I hoped that maybe I would be able to hide there. I crawled like that for several hours and then became very tired. Then I heard a noise among the stalks. I jumped up in terror, and to my great surprise, before my eyes I saw Yeshiye [Shaya]Zweigman and Hershel [Harry]Fish. We cried bitterly over our painful situation, and began to think about where we could go, where to hide. Meanwhile, we decided to stay in the field and see what we could do to save ourselves.

For more than a month, we remained like that, among the corn stalks in the field. We sustained ourselves with radishes, carrots, and other greens. We trembled at every sound that we thought we heard. So we decided to go to the closest village Podszkodzie, which was about six kilometers from Ostrowiec.

It was evening. I went to a peasant whom I knew, Sliwka. Zweigman and Fish remained lying behind the barn, because I thought that if the peasant would see three people he would chase them out. The peasant became frightened as he saw how lost I looked. He helped me wash up and brought me something to eat. It got late. I asked that he allow me to spend the night, so he took me into the barn and told me to go to sleep on the hay. When he left, I opened the gate and told Yeshiye and Hershel to come in.

The following day, I went into the peasant’s hut and asked him to let me hide in his place. The peasant Sliwka was willing to let me hide there, but his wife, with tears in her eyes, turned to me and said:

“Mr. Waldman,” she pleaded with me. “You already lost your wife and children. I have my family here, and if the Germans will find you here, they’ll shoot all of us…”

The peasant Sliwka tried to calm her down. “So, let Mr. Waldman hide in the barn. You’ll see,” he tried to reassure her, “the war will end and the Jews from America will reward anyone who helped save a Jew.” I was able to reassure the woman, that I would hide in the barn unnoticed. But when the peasant came into the barn and saw two more people, he became very angry and told all of us to get out of the barn.

I had left money with the hotel owner, Mr. Radzicki, and knowing that the peasant liked bitter drops [bits of money], I calmed him down by giving him a note to give to Mr. Radzicki, telling him to give the peasant money in my name. That night, the peasant came back from town quite drunk, created a scandal, and we trembled that he should not reveal that he was hiding Jews in his barn.

The following morning, the peasant Sliwka came to us, brought us food, cleaned a place for us in the barn, and assured us a place by him. He heard in town that the Russians were getting closer to Poland, and he said he would save us. We stayed in the barn with the animals for about six weeks, until it became cold. Then the peasant dug up a pit in the field and took us there at night.

We stayed in that living grave for about six months. It was hot in the pit, so we sat completely naked. At night, the peasant would bring us food. For that entire time, we did not see the light of day. The top of the pit was covered so that it could not be noticed that someone was hiding there. We became like savage men, with overgrown hair, and we were terrified at the slightest sound outside over our heads. Very often, the peasant Sliwka would come back from Ostrowiec drunk, and we were terrified that he would give us up. Many times, we heard the Germans come and take animals and other food from him. We heard their shouts and voices over our heads. It is impossible to describe in words how we felt at that time…

In the living grave, we completely lost the ability to feel or think. But some sort of hidden spark burned in our minds, which gave us the hope to save ourselves. There were days when the peasant completely forgot about us. At that time, we would often become disoriented, and we wanted to get out of the pit and die with the rest of the Jews. But the will to live was stronger, so we would make plans that one more day, and one more day, and we would be saved.

One evening, the peasant Sliwka came into the pit, brought us food, and told us that the Russians were getting closer, and that in Ostrowiec, you could already hear the shooting. This news created a major upheaval in us, such a small thing: to be freed! We immediately began to think about what we would do. Suddenly we began to feel like people again. Ten days later, the peasant Sliwka opened our living grave and told us that the Russians were already in the village. We washed up and left to Ostrowiec.

I went to the hotel of Mr. Radzicki. The hotel was occupied by the Russian military, but he nonetheless found a room for me. A few days later, some Jews were shot by a Pole, one of these Jews was my cousin Leibel Lustig. He survived, but needed medical attention. I knew that there was a Russian military doctor in the hotel, so one day I knocked at his door, and as soon as he saw me, he told the servant to leave. He locked the door, fell onto my neck, and began sobbing. He spoke Yiddish to me: “I am also a Jew,” he began with tears. “How did you manage to save yourself? I saw the great tragedy that struck our nation everywhere. Flee from here as quickly as possible, the Poles will kill all of you.” Two days later I left for Krakow, from there to Italy, and from there to Canada.

To this very day, we have not forgotten the peasant Sliwka. The three of us always send him clothing, food, and medicines. Two years ago, we brought his daughter over to Canada, and married her off here. She lives in London, Ontario, where I live. We fill all the peasant’s requests with joy. We thank him for our lives.