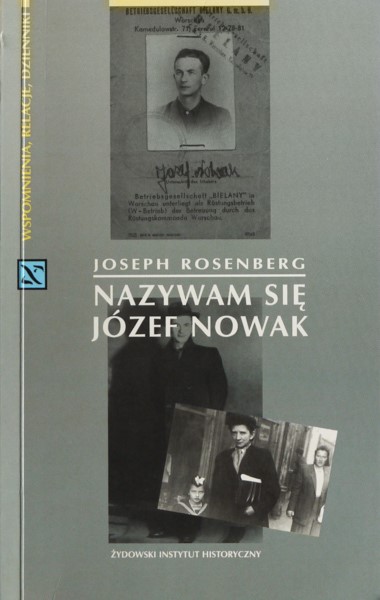

Joseph Rosenberg

Researched and Edited in Polish by Wojtek Mazan. Translated from Polish with assistance of Google translate.

The Polish article from Wojtek's blog can be found here.

Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw 2004

pp.11-12

when peasants from nearby villages came to sell their goods on the market. When they left home at the end of the day, their cars were loaded with goods purchased from Jewish traders.

Most of the Jews from Ostrowiec were very orthodox. According to tradition, handed down from generation to generation, they worked hard during the day and studied the Torah in the evenings. In 1888, a new spiritual leader arrived to the city, Rabbi Mejer Jakiel Halawi Halsztok . He was worshiped by his community for doing good, he soon became known beyond the borders of Ostrowiec as a man of great wisdom and righteousness. At the beginning of the twentieth century, he became famous in the Jewish world as an "Ostrowiec rabbi". He maintained this title until his death in 1929, reaching the age of 79.

My grandfather, Chaim Rosenberg, was born in a rich Ostrowiec family. He was the owner of a farm and a mill. His son Froim (later Frank), and my father, was born on this farm. In his youth, his parents sent him to the famous Yeshiva in Vilnius, where he studied Torah. There he became very religious, praying with such enthusiasm that he more closely resembled an actor who was singing his issues in a solemn way than someone praying. And what a beautiful voice Froim had! It was so unusual that people would stay outside the synagogue during the most important Jewish holidays, just to hear his singing.

Thanks to his family fortune, Froim did not have to go to work after returning to Ostrowiec, but he could spend most of his time in the synagogue studying the sacred books. However, when the mill burned, he lost his source of income and had to find a different way of earning money. Soon he married Brandla Flicker, a beautiful young heiress to the wealthy Ostrowiec family, whose dowry was so large that it enabled him to open his own business, involving the trade of imported fruit and sweets.

pp. 18-19

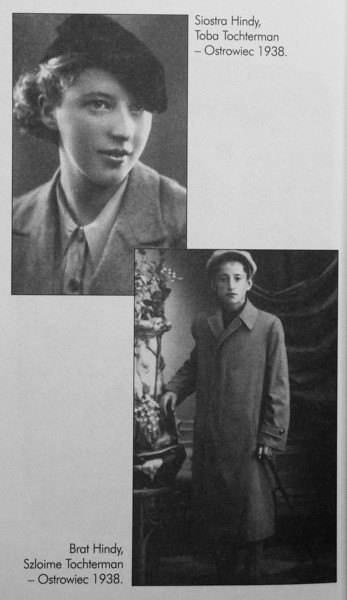

"In Ostrowiec I lived with my grandmother on my father's side, I also spent a lot of time with my aunt Miriam Rapoport, whose husband Mojsze helped me to regain my mother's grandmother's fall, and suddenly I gained material security and my family came to the conclusion that I should marry. a lot of time, when they found the right szidoch (party) for me, the girl they chose was Hinda and she was a seventeen-year-old daughter of Aron and Perl Tochterman.

We got married in 1931. After the wedding, we lived in one of the rooms in her parents' house, sharing the first floor with two Hindi brothers, Szloim and Chiel, and sister Toba. After living there, I took up work for my father-in-law who was the owner of the Esperanto Confectionery Factory, a confectionery factory with a long tradition, located on the ground floor of our building.

The Tochtermans were a well-known and respected family of Ostrowiec, very religious and very generous. Every Friday, they invited a poor street farewell to dinner. On every Sabbath in the morning, before going to the synagogue, we ate a special breakfast consisting of eggs and bread with butter sprinkled with chopped chives and onions. On Sabbath afternoons, our family used to pay visits to relatives living in our town. Life was simple and harmonious and flowed with almost no changes from year to year.

In 1933 our first child was born - a daughter whom we named Brandel in honor of my mother. Two years later, on July 27, 1935, our son Jakub was born (later changed his name to Gerald).

Esperanto Confectionery was a thriving family business that was even more successful after 1936, when I introduced a new type of candy, similar to Lifesaver candy. We had to develop a company to be able to produce these and other goodies enough to cover the entire country's needs. After buying a piece of land on the town's outskirts, we built a new two-storey building, which was ready for development in 1937. The factory, equipped with the most modern machines and equipment, was located on the ground floor. There were several apartments on the first floor, one of which we occupied and the other one we rented.”

pp. 21-22

"In the early morning of September 7, 1939, German armored cars and tanks rolled into Ostrowiec, and immediately after the Nazis seized the town, a large Hebrew school closed its doors." Soon, the SS established the Judenrat, the Jewish Council, ordering it to collect contributions from Jewish population and confiscation of property.

Unexpectedly, at the very beginning, the Germans were quite friendly to us. Not only did they allow us to run the factory - of course, after bribing their superiors with expensive presents - but they also agreed to supply us with sugar and other ingredients necessary for production. We just had to take out a certain contingent of sweets for their soldiers.

I was a realist and knew that our days are numbered, and that sooner or later the factory management will be appointed Treuhänder, a non-Jewish supervisor. In order to win a trustworthy person who is finally to take over our factory, I turned to Mrs. Kwiatkowska, the wife of a tax collector. Shortly before the outbreak of the war, she and her husband were our tenants. When Mr Kwiatkowski was transferred to another city he did not like, he asked me to use his influence in the city council and arrange for him to be transferred back to Ostrowiec. At my request, city councilors wrote to the tax authorities, in which it was written that Mr. Kwiatkowski's services are necessary in our city. Because I made it possible for him to return, it seemed quite logical that I should choose his wife as a factory supervisor. Particularly important was the fact that she was a German woman and had two brothers in the Gestapo, who used their influence to get her position. That's how Mrs. Kwiatkowska became Treuhänder of Esperanto Confectionery.

I made arrangements with Mrs. Kwiatkowska in the following way: together with my father-in-law, I was to continue to run the factory under its supervision and to supply the Germans with obligatory contingents. Knowing that sugar, as a dry ingredient, in the final phase of production weighs about 7 percent more due to the water content, I suggested to Mrs. Kwiatkowska that we sell surplus sugar on the black market and divide the profits into three parts: for her, her father-in-law and for me.”

pp. 25-26

"Having regard for the safety of my children, I asked a Polish friend to take in our oldest daughter Brandla, I was convinced that a generous payment would guarantee proper care for the child." This turned out to be the biggest mistake of my life, as soon as the Germans announced that they would shoot every Pole. who will be holding a Jew, a terrified woman chased Brandla out of the house. The child wandered around the city for some time until it was found by the Polish police and handed over to the Jewish police operating in the Ostrowiec ghetto.

When I learned that only young, physically fit people, able to work for the German war industry would be able to stay in the ghetto, I contacted Awrom Kerbel. Awrom Kerbel was a Jew managing a labor camp located in nearby Bodzechów and similar to the one described in the Schindler's List. Believing that work there can ensure my survival, I made the following "arrangement" with Awrom: he will register me and his wife as normal prisoners - her as a sorter of clothing, me as a construction worker.

[...] I focused on finding a safe haven for the youngest daughter Henia. I decided to turn to Błażej Wawrzoska, a long-time caretaker employed in our factory, whom I felt I could trust. He agreed to take the child whom I brought to his home on October 7, 1942. Although at that time I was not allowed to work in the factory, I asked Aleksander Kwiatkowski, who replaced his wife as manager, to pay Wawrzosk a thousand zlotys a month for taking care of little Henia.

Without feeling safe in Ostrowiec, I decided to move to Wolbrom. [...]

[...] I left Ostrowiec at night, which later became history as the "night of black daggers" because murder was committed on many innocent people this night.”

Page 31

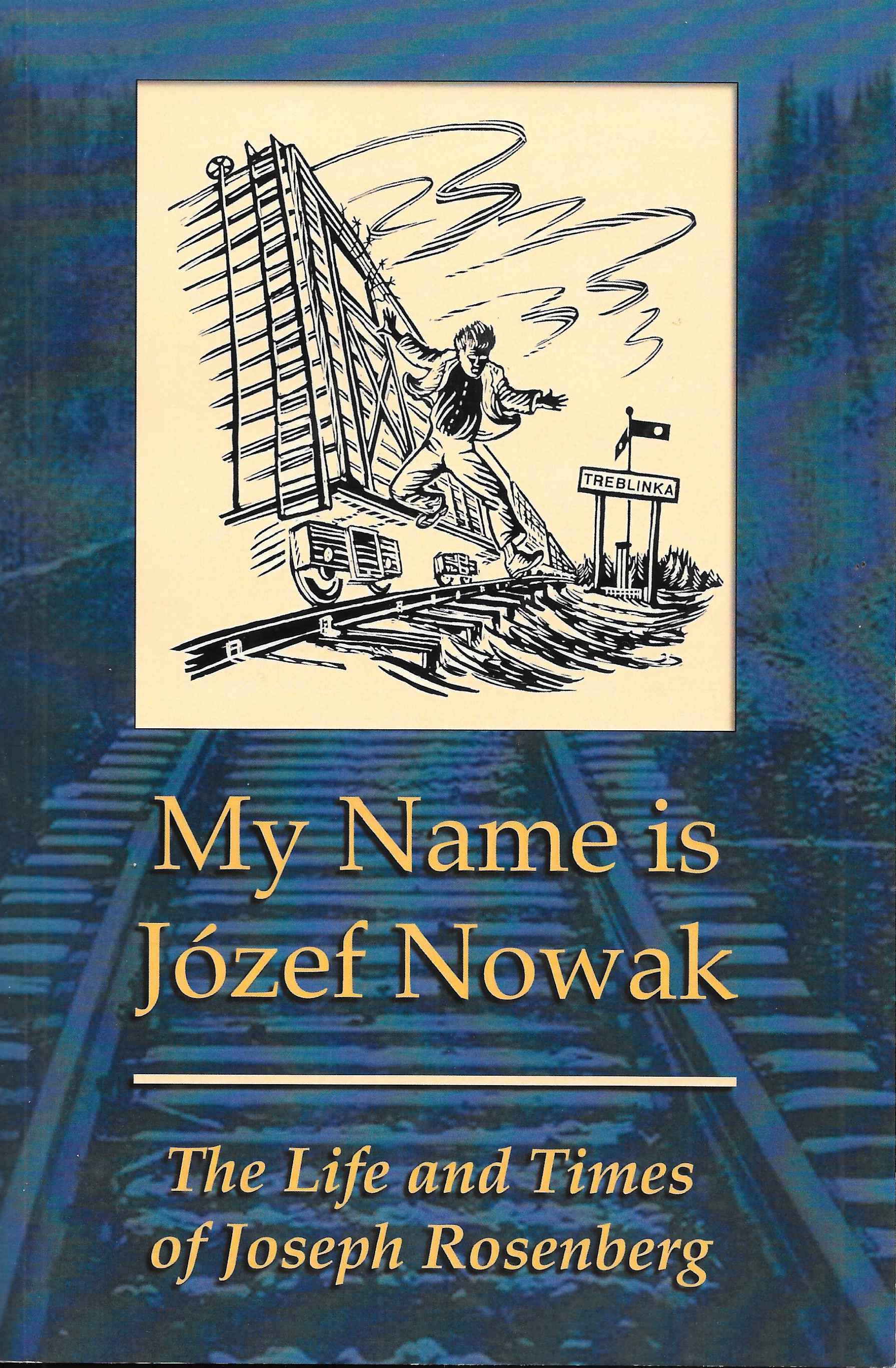

"On the night of October 11 and 12, 1942, the Germans liquidated the Ostrowiec ghetto, murdering more than a thousand Jews, most of them children, the elderly and the sick, and the remaining 11,000 to Treblinka for a certain death." My daughter Brandla was probably among them, Later I found out that my father-in-law was begging the Jewish police to let her out, unfortunately to no avail.

In December 1942, Gerald and Hinda were sent to Sandomierz, one of the worst Nazi concentration camps. Shortly after arriving at the scene, they witnessed a horrible scene. The dark and stormy night the Germans had driven to the market, along with other prisoners, had to watch the execution of the son of the well-known rabbi of Ostrowiec [Rabbi Yechezkel Halevi Halstock]. When he arrived, dressed in a black caftan and broad-brimmed hat, traditionally worn by orthodox Jews, his beard was covered with a towel because the Germans regarded the beard's view as repugnant. Having on his left and right side one of his followers, he walked fearlessly, reciting Kaddish along the way. Suddenly, without any warning, a group of Ukrainians, who were part of the hated Stafkommando, dragged him to the very center of the market. Agreed with the fate that awaited him, he looked into the eyes of his tormentors. For a split second they seemed to hesitate to pull the trigger. When it was after all, they looked more terrified than their victim.”

pp. 71-72

"The Red Army liberated Ostrowiec on January 16, 1945. Jews who lived there before the war and survived the Holocaust had an open way back, although they could stay there permanently, many decided to go from other places, or generally leave Poland.

I returned to Ostrowiec to see if any members of my family survived. Of course, I was devastated when I found there only men and women, vaguely known from the past, who flowed into the city after years of war spent in hiding. In addition, I wanted to know what had happened to my factory, which, as I was told, produced sweets for German soldiers throughout the war. After the retreat of the Germans, the factory was taken over by the Russians, they exchanged the ground floor for a warehouse and shared the first floor for a bakery and a military hospital.

[...] After arriving in Ostrowiec and moving into our old house at 64 Pierackiego Street, I did everything to build a new life for Gerald and himself.

As per Rita Rosenberg:

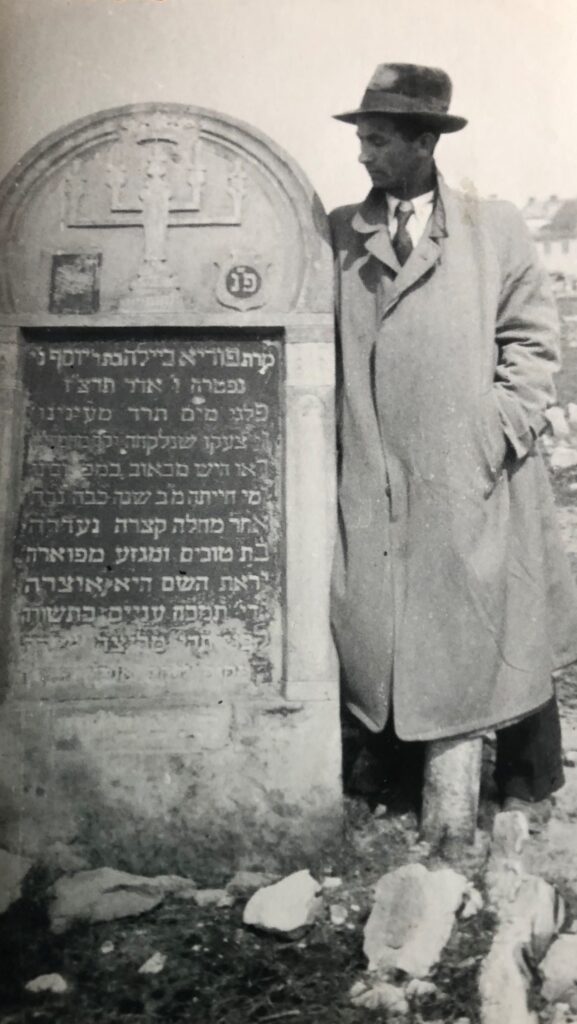

My father Joseph Rosenberg and my brother Gerald are on the left. My mother, Hindala is beside the monument. Beside her is Jack Rapoport and in the forefront is Jack’s sister Dorothy Rapoport Stern.

pp. 73-74

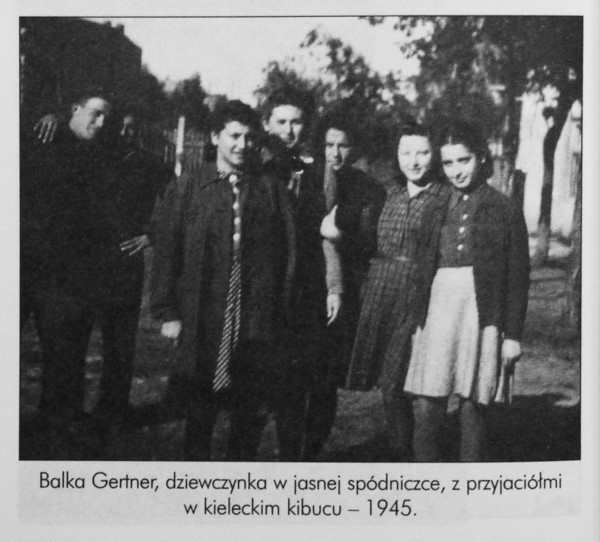

"A wonderful surprise was the return of my cousin Jacek Rapoport, brother of Dorothy from Buchenwald , he stayed with us for some time, just like Gela Katz before going to Israel, which was a dream come true for her." Another welcome guest in our house was Bajla, daughter of cousin David Gertner. I had a lot in common with him. He also saved himself by escaping from transport to Treblinka. He even managed to return to Ostrowiec to his wife, but soon after his return they were both taken to Auschwitz and their hearing was lost. Bajla, who avoided the extermination camps, left us to work in a Zionist organization in Kielce. Unfortunately, she and forty-one other Jews were brutally murdered there during the pogrom, organized by the residents on July 4, 1946.

"Together with Aron Friedenthal who also managed to survive the war, we set up a help committee to ensure that Jews returning to Ostrowiec a substitute for a normal life. The success of our mission can only be owed to Russian officers of Jewish origin who were stationed in our city. Not only did they provide everyone with free food and decent accommodation, but they also made sure that the soldiers under their command treated us duly. These officers also helped me get along with the Russian authorities and arrange for the factory to be handed over to me. It is to be understood that I was happy when they left her on the appointed day. However, it was a shock to discover that all her equipment had disappeared. Because the recovery of the machines was doomed to failure, I published a few announcements in the local press that I would like to buy used confectionery. Suddenly, various people began to report, offering me the purchase of this or another device. What should I do? I swallowed my pride and paid everyone for it ganowim (thieves) salty money for things that they stole from me earlier. Soon, with my partner, Awrom Berman, the son of the founder of Sweets, Amora , a large pre-war confectionery company with a long tradition, we started the production of sweets and cakes.”

Joseph and Hinda's youngest daughter, Rita, was born in Ostrowiec on May 28, 1941..

At 16 months old, she was given to a Polish family for safekeeping. However, the Germans soon announced any Poles found hiding a Jewish person would be killed, and the family had a brother-in-law take Rita to another town.

She was found abandoned on a train a few miles southeast of Ostrowiec, in a town called Razwadow. A Polish couple adopted her.. When the war was over, Joseph father set out to find her, tried multiple methods to get her back and was finally returned to her biological parents. The family left Poland to Toronto, Canada.

Rita Rosenberg Starkman - Joseph's daughter Rita is interviewed here about her Holocaust story